Feedback From Laptop Speakers

Let the worship music be heard without distraction.Photo provided byYou might be suffering from all three of these audio feedback problem areas. I’ve been emailing a sound tech overseas who has had feedback problems. In my initial email, I said it could be caused by one of a few things. As it turned out, he had all three conditions that were causing feedback. Let’s get it workFeedback is caused when a particular frequency becomes excited and is thus astronomically amplified causing the screeching and howling sounds.

Reminds me of Halloween. But seriously folks.the feedback usually occurs when a sound is loud enough to be amplified by a stage monitor and then picked up by a microphone and gets into an amplification loop. In this loop, the amplified sound gets louder and louder untilSCREEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEECH!

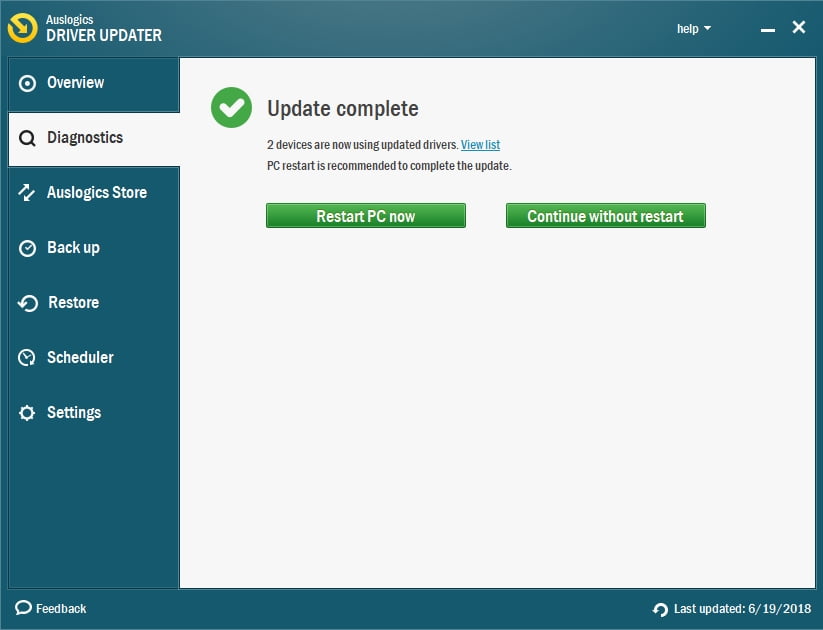

A bad audio configuration on your computer might leave you wondering if there's an echo in the room. The computer's audio settings can create a feedback loop that repeats played audio through the.

The Three Easy Ways For Preventing Feedback 1. Place microphones in the right relationships to loudspeakers and monitors.In the case of my overseas friend, his church setup had the pastor’s vocal microphone out in front of the house speakers. While such a scenario can work without having feedback, it’s a scenario that’s much more likely to experience feedback.

This is especially true if the pastor moves the microphone or turns in a way that his/her body is no longer blocking sound between the house speakers and the microphone.Regarding floor monitors, vocalists should be very close to their floor monitor. The monitor volume should be loud enough that the musician can hear it but not so loud that the microphone picks up the sound when they are holding it up to their lips.Tip: Ask your singers not to drop their microphone to their side when they take a break. Rather, ask them to first move away from the monitors and then they can lower their microphone. Otherwise, they are essentially stuffing the microphone into the monitors and then it’s feedback city! Teach musicians to use the proper vocal microphone technique.Last Saturday, I taught a 4-hour audio training course at a local church. I explained that anyone using a vocal microphone needs to hold the microphone right up to their mouth. Immediately, two of the people in the class started talking about how certain people would start with the microphone up to their mouth and slowly lower it as the song went on.

They’d have to turn up the gain untilSCREEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEECH!People using vocal microphones need to know that audio equipment has its limitations. Therefore, explain to the singers that if they lower their microphones their voices will drop out of the mix.

Regarding people using vocal microphones for speaking roles, it’s a bit easier. The problem I’ve observed is, like the singers, they slowly lower the microphone. As they are using the microphone for a speaking role and will likely be holding a bible, book, or piece of paper, set up a vocal microphone on a stand for them. Have them read a bit after the sound check to set the gain.Tip: If you have more than one person talking into the same vocal microphone during the service, make note of their natural speaking volume level.

This way, when they walk up to the microphone, you can lower the fader before they speak those first words. Use the proper gain setting technique.Setting the channel gain for any sound source, you want the clearest strongest signal. You want the best signal-to-noise ratio so that the sound, such as the singer’s voice, is stronger than any line noise that might exist. However, you don’t want to allow for so much gain that you allow for feedback in the system.An easy way to get the best signal-to-noise ratio is by using the “gain-before-feedback method” of gain setting. As you turn up the gain, with the fader at 0, turn it up until you get feedback. Then turn down the gain a few notches.

Personally, I set the fader at zero and turn up the gain until the sound is about at the volume where I want it in the room. But if I do experience feedback, I know to turn back the gain. The Take AwayIf you find you are having more than your share of feedback during an event, consider more than one issue might be the problem. Feedback prevention comes down to placing microphones in the right relationship to monitors and loud speakers, ensuring that microphones are as close to the sound source as possible, and that you are sending the right amount of the audio signal into the mixer.One last very important piece of information. As I told my class on Saturday, the entire sanctuary is your responsibility.

This means everything from the stage to the sound booth. The next time you experience a feedback issue and are asked about it after the service, don’t place blame on someone else or some piece of equipment. Take ownership of it, apologize for it, and do what you can to prevent it from happening again. I have issues with my lapel mic at church. I cannot get any volume on it without turning the EQ’s way down. I mean down to the point where everything is around -10/15 from lows all the way to highs.

If I apply an EQ mix to it, it gives me terrible feedback. I also have a hard time getting my podium mic to pick-up the voice properly to project the volume out to the house speakers with out getting feedback. I’m pretty new at running the sound at my church and I don’t know if I should be using compression, gates, High/low pass filters, etcso input on these situations would be a major blessing to me. I read this “Feed Back” article hoping I can get one of our volunteers better aware of how to control/avoid it. While I can’t say I’ve never encountered feedback, I would say I have it pretty well under control.However, I don’t agree with your suggestion to place a microphone to the lips of a singer/speaker.

We usually use wired and wireless versions of Shure 87s (old and new wireless versions). All three versions will pick up siblance (sp?) sounds and “P”oping and breath-wind noises when placed directly in front of and close to our singer’s lips. We also bet a much more bassy sound because of being so close to the hollow mouth! I use one of two methods to try and avoid these disturbing sounds. 1: I try to get the user to lower the mic to their chin or 2: move the mic to one side of the mouth. The point is to get the mic out of the direct wind of the users mouth and away from the echo chamber of the mouth.One reason this is a constant problem is that users continue to see images of singers ‘eating’ the mic.

I don’t know what brand/model mic these singers are using. And the extra bass (presence) is good in certain types of singing, but few churches need a nightclub effect!;-)Do you have a different approach I could use with these mics? Again, we very seldom have feedback problems but I’d like to have another method that could make our job easier AND more successful!Thanks for your great site!!

Jim, the singers can have the mic up to their lips but still sing over it. The plosives and the proximity effect (more bass the closer to the mic) can be resolved with a little EQ work. The farther away the singer’s voice from the microphone, the more gain you have to give the mic.

Feedback From My Laptop Speakers

Then you are picking up more sound on the stage (drums, amp’s, anything else).We sometimes put a backing singer near the drummer so listening closely to that singers channel, I can hear the drums. I’ll add a gate to their channel so when they aren’t singing, the channel automatically drop the dB level of the channel so I don’t get the drums coming through that vocal microphone.

Check out this article on. Hi,Overall this is a good article. The only suggestion I would have is adding to the mic placement relationship section is mentioning something specifically about polar pattern and mic selection.

In the spirit of prevention, understanding that using 2 wedges with a supercardioid mic will have less potential for feedback than with a cardioid pattern. Conversely, a supercardioid pattern with a single wedge is less effective that a cardioid mic. Most people don’t have a clue about polar patterns.Just a thought.

By Shure Notes Editors. Contributors: John Chevalier, Bill Gibson, Frank Gilbert, June Millington, Dan Murphy'John had a semi-acoustic Gibson guitar. It had a pickup on it so it could be amplified. We were just about to walk away and listen to a take when John leaned his guitar against the amp. He really should have turned the electric off. It was only on a tiny bit and John just leaned it against the amp when it went 'Nnnnnwahhhh!'

And we went, 'What's that? 'No, it's feedback.' 'Wow, it's a great sound!' George Martin was there so we said, 'Can we have that on the record?' It was a found object, an accident caused by leaning the guitar against the amp.'

– Paul McCartney (Source: Many Years From Now, Barry Mile)It's pretty much common knowledge among students of pop music that The Beatles' 1964 recording of 'I Feel Fine' was one of the first known examples of feedback as a recording effect, even though The Kinks and The Who reportedly (and intentionally) used it in live performances. For most musicians and engineers, though, audio feedback is something to avoid.In this post, we'll cover some of the fundamentals – what causes feedback and how to avoid it - along with tips from some of our favorite audio pros.What is acoustic feedback?Acoustic feedback occurs when the amplified sound from any loudspeaker re-enters the sound system through any open microphone and is amplified again and again and again. We've all heard it – it's that sustained, ringing tone, varying from a low rumble to a piercing screech.What causes itThe simplest PA system consists of a microphone, an amplifier and one or more speakers. Whenever you have those three components, you have the potential for feedback.

Feedback happens when the sound from the speakers makes it back into the microphone and is re-amplified and sent through the speakers again, like this:Here's an example: Let's say that that you place the microphone in front of the speaker as shown here. If you tap the microphone, the sound of the tap goes through the amplifier, comes out the speaker and re-enters the mic. This feedback loop happens so quickly that it creates its own frequency, and that produces the howling sound — an oscillation triggered by sound entering the microphone. Placing the microphone too close to the loudspeaker, too far from the sound source, or simply turning the microphone up too high all raise the likelihood of feedback problems.Pro Tip #1'The worst is vocalists who cup the mic capsule (e.g.

Rappers who put their hand around the grill of the mic because they think it looks cool). This invariably makes the mic sound horrible and very susceptible to feedback. More importantly, it changes the directional nature of the microphone, changing it to essentially an omnidirectional microphone.

One trick is to cut everything from 800 Hz to 2 kHz, compress it, and hopefully the horrible howling sound will go away and the vocals will still be intelligible. But don't forget, the best thing to do to control feedback is turn everything down.' – Frank Gilbert, FOH Engineer Park West, The Vic Theater, and The Mayne Stage - all in ChicagoSuggestions on how to interrupt the feedback loop. Move the microphone closer to the desired sound source.

Use a directional microphone to increase the amount of gain before feedback. Reduce the number of open microphones – turn off microphones that are not in use. Don't boost tone controls indiscriminately. Try to keep microphones and loudspeakers as far away from each other as possible.

Lower the speaker output. Move the loudspeaker farther away from the microphone. Each time this distance is doubled, the sound system output can be increased by 6dB. Move the loudspeaker closer to the listener. Each time this distance is halved, the sound system output will increase by 6dB.

Use in-ear monitoring systems in place of floor monitors. Acoustically treat the room (if possible) to eliminate hard, reflective surfaces like glass, marble and wood.Pro Tip #2'In a well-designed system, the irritating high-pitched brand of feedback isn't much of a problem unless someone points a mic into a monitor.

So long as the performers are careful to always keep their mics pointed away from the monitors, or specifically to point that tail end of the mic at the monitor at all times, that shouldn't be an issue.' –, author of over 30 books, producer, performer and Berklee School of Music faculty memberWhen these solutions have been exhausted, the next step is to look toward equalizers and automatic feedback reducers.Ringing OutA common technique used by sound engineers is 'ringing out' a sound system by using a graphic equalizer to reduce the level of the frequencies that feedback:. Slowly bring up the system level until you begin to hear feedback.

Now go to the equalizer and pull down the offending frequency roughly 3dB. If the feedback is a 'hoot' or 'howl', try cutting in the 250 to 500 Hz range. A 'singing' tone may be around 1 kHz. 'Whistles' and 'screeches' tend to be above 2 kHz. Very rarely does feedback occur below 80 Hz or above 8 kHz.

It takes practice to develop an ear for equalizing a sound system, so be patient. After locating the first feedback frequency, begin turning up the system again until the next frequency begins ringing. Repeat the above steps until the desired level is reached, but do not over-equalize. Keep in mind the equalizers can only provide a maximum level increase of 3 to 9 dB.Pro Tip #3'The last time I experienced feedback was in a small venue where I was onstage.

As a musician and an audio tech, I'm a sound guy's worst nightmare. During rehearsal, my headset mic was feeding back and the audio tech kept turning my volume down and telling me that I couldn't move around. I knew the problem was midrange feedback, so I explained to him that if he just lowered the midrange on the EQ, the problem would go away.

He 'passionately and firmly' explained to me that the only way to get rid of feedback was for him to lower the volume and for me to stand still.After enduring the first song, I walked back to the board, reached over his shoulder and dropped the midrange. I sang a couple notes, looked at him, smiled and walked back onstage. (Did I mention I was wireless, too?) The problem was solved and we didn't talk after the set, but I know he learned something that night.' –, pro audio/video expert, writer and speaker at InfoComm, NAB and other industry eventsPro Tip #4'If there's one thing I've learned in all my years of playing, it's that the sound engineer has to be extraordinarily vigilant even about protecting the performers' hearing.My last bad feedback incident was caused by gain stage being manipulated by the engineer without telling us - after we'd gotten to a good place. The resulting, shrieking feedback changed everything - there was nothing but pain filling up space between our ears. Many people forget that EQ'ing something can cause a volume change - right in that frequency.Of course, EQ can remedy volume problems quite easily. Just take a moment to ferret out the offending frequency or cluster of frequencies - band members protecting their ears, of course - and 'forensically' attenuate, which will immediately solve the problem.

A hall of mirrors, isn't it?' – June Millington, FANNY frontwoman, musician and songwriter, co-founder ofAutomatic feedback reducers are very helpful in wireless microphone applications. Remember that microphone placement is crucial to eliminating feedback, and the temptation to wander away from the ideal microphone position when using a wireless is great. If the performer gets too close to a loudspeaker, feedback will result; a good feedback reducer will be able to catch and eliminate the feedback faster than a sound engineer.Pro Tip #5'The best 'gear' a sound person has is his or her ears. Learn to identify the ringing frequency by doing blind 'what is that frequency?' Tests using a sine wave generator or test tone generator. Have someone dial up a tone and see if you can identify what frequency it is.

This is great training to identify the problem frequency during feedback howl and how I learned how to tame feedback.' – Dan Murphy, Sound Tech Director, Lakeside ChurchNOTE: Don't rely on an equalizer/feedback reducer alone to provide sufficient additional output in a sound system where the microphones and loudspeakers are too close together. You probably won't get the results you need.

Select input and output folders to process every package in the folder. As of version 2.3 it will also optionally convert subfolders in the input folder, creating corresponding subfolders in the output folder if necessary. Texture output options: Choice of which conversion to do and the target texture dimensions should be self-explanatory. Is it possible Maxis'd release one for Sims 4? A High Resolution Texture Pack? Senbre Posts: 996 Member. I'd certainly be interested in an optional HD texture and lighting pack too. CK213 Posts: 17,892 Member. February 2015. I would be first in line. It would make sense in a way. Skyrim seems to have had consoles as a first. The Sims 3 was so good that even with The Sims 4 released in the world, players all over still go back to the beloved game. That means that mods are essential to the experience, as it is an older.  Although The Sims 3 Graphics may look old to some, there are still a few tweaks that you can do to improve your visual experience of the game. Shadows Quality Even with all Settings set up to max, it still might feel like Shadows are not showing their full potential. They appear jaggered and distorted. Understand that this mod, indeed all HQ mods, are for enhancement. They are not a replacement for a good video card. They are not going to give you phenomenal graphics if you don’t already have that capability. HQ mods are intended for close-up graphic enhancement of the Sims themselves.

Although The Sims 3 Graphics may look old to some, there are still a few tweaks that you can do to improve your visual experience of the game. Shadows Quality Even with all Settings set up to max, it still might feel like Shadows are not showing their full potential. They appear jaggered and distorted. Understand that this mod, indeed all HQ mods, are for enhancement. They are not a replacement for a good video card. They are not going to give you phenomenal graphics if you don’t already have that capability. HQ mods are intended for close-up graphic enhancement of the Sims themselves.

For more information, read our post.